A Brief History of Surveillance in America

With wiretapping in the headlines and smart speakers in millions of homes, we take a look back to the early days of eavesdropping. “Americans have come to terms with the inconvenient truth that there is no such thing as electronic communication without electronic eavesdropping,” says Hochman, a 2017-2018 National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar, who is currently writing a book on the subject. With wiretapping in the headlines and “smart” speakers in millions of homes, we asked Hochman to take us back the early days of eavesdropping and to consider the future of “dataveillance.”

How far back do we have to go to find the origins of wiretapping?

It starts long before the telephone. The earliest statute prohibiting wiretapping was written in California in 1862, just after the Pacific Telegraph Company reached the West Coast, and the first person convicted was a stock broker named D.C. Williams in 1864. His scheme was ingenious: He listened in on corporate telegraph lines and sold the information he overheard to stock traders.

Who’s been doing the eavesdropping?

Then, the 1930s brought revelations that wiretapping was a widespread and viciously effective tool for corporate management to root out union activity. The La Follette Civil Liberties Committee in the United States Senate, for instance, found all sorts of wiretap abuses on the part of corporations. Hiring private detectives to spy on labor unions was one of the classic dirty tricks of the period.

When did the general public become concerned about issues of wiretapping?

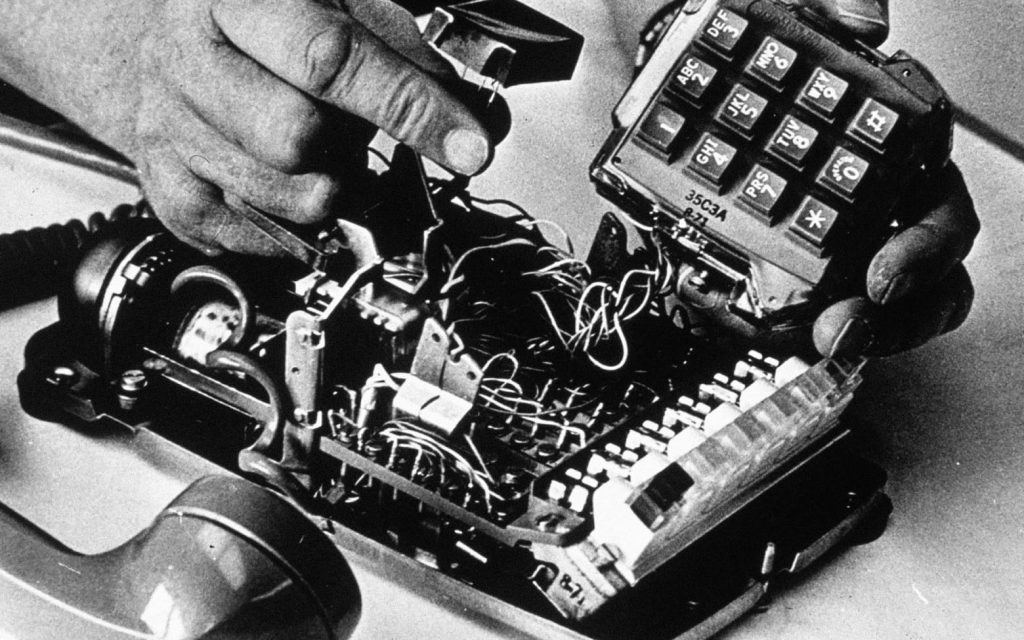

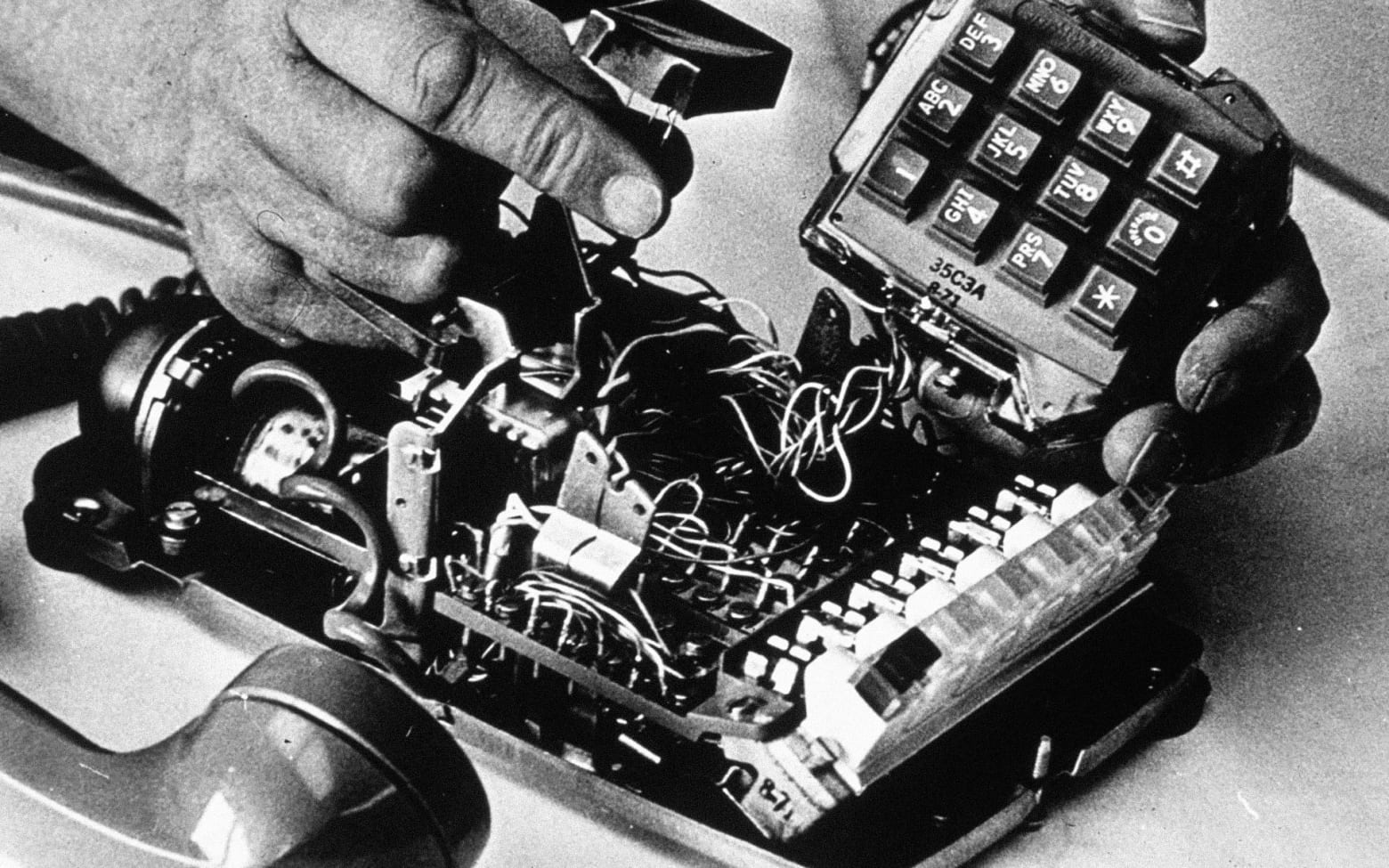

It’s only in the 1920s that ordinary Americans start to take notice of wiretapping and it’s not really until the 1950s that it’s seen as a national problem. Even then, it’s mostly the issue of private wiretapping that concerns people. Wiretapping for hire was extremely common in certain locations, most famously in New York. It was legal, for instance, under murky one-party consent laws to hire an electronic surveillance specialist—known as a “private ear”—to tap your wires to see if your wife is carrying on with another man. Needless to say, the American public was worried about this army of unofficial actors who had the ability and the know-how to tap into the rapidly expanding telephone network.

Feelings were mixed about “official” wiretapping. By 1965, the normative political position in the United States was that wiretapping for national security was a necessary evil, whereas wiretapping in the service of the enforcement of criminal law—in, say, tax evasion cases or even in Mafia prosecutions, which was a big priority among American law enforcement starting in the 1960s—was outrageous and an abuse of power.

Today, it’s the opposite. Most people are worried about wiretapping by the government.

That started with Watergate, when the public saw abuses of wiretapping by the executive branch, and it has spiked again with the Edward Snowden revelations about the National Security Agency. But it’s important to realize that today there are almost two times more warranted wiretaps carried out for criminal investigations than for national security ones. Since wiretapping in criminal investigations disproportionally targets African-Americans and Latinos as part of the “war on drugs,” it isn’t just a civil liberties issue; it’s a civil rights issue.

What does the 150-plus-year history of wiretapping reveal about the issue today?

There is something categorically different about electronic surveillance in our contemporary moment: the extent to which it operates on a mass scale. Wiretapping and electronic eavesdropping was highly individualized up until the 1980s. We were tapping individual telephones and listening to individual conversations. Now, as a result of the rise of “dataveillence” in particular, we’re talking about a scale of surveillance that scarcely seems fathomable from the perspective of the 1960s, 1970s, or even the 1980s.

Dataveillance is the tracking of metadata. The NSA does listen to people’s conversations, which is what we traditionally think “wiretapping” is, but far more often the NSA tracks the data of those conversations. What’s important isn’t necessarily what you said on the phone but who you called, when you called, where your phone is, the metadata of your financial transactions—that sort of stuff. They triangulate a million different data points and they can come to a very clear understanding of what has happened.

But one of the areas in which there is a continuity from even the earliest days of wiretapping, is the extent to which telecommunications industries are complicit in the rise of a surveillance state and the extent to which surveillance data flows between the telecommunication infrastructure and the infrastructure of American law enforcement. The easiest way for law enforcement to tap wires in the 1920s in the service of the war on alcohol wasn’t to actually go and physically tap a wire but to listen in through the Bell System central exchange. Bell publicly resisted complicity in that arrangement, but that’s what happened. It’s the same today.

Yet people are willing to let companies eavesdrop on them.

Those smart speakers? They are essentially wiretaps. They are constantly listening. It’s a new type of corporate surveillance: If they listen to you, they can get you what you want, when you want. People like that. But where else will that data go?

What will happen next?

Historians are not in the business of prognostication, but the one thing that I can say with some certainty is that electronic surveillance and dataveillance are going to scale. They will be more global and more instantaneous. I can say with much more certainty that that public attention to these issues will wax and wane. This is one of the things that is so striking about the history of wiretapping in the United States: It has never been a secret, but it’s only every 10 to 15 years that there is a major public scandal surrounding it. There are these brief moments of outrage and then there are these long moments of complacency, like now, and that is one thing that has enabled surveillance to persist in the way that it does.

source: Smithsonian